Cats!

Curated by: Christina Kim and Shirly Huilian Zhang

Cats. Popular images of the kinds we live with range from warm, cuddly and purring, to solitary, disdainful and remote. Their gentleness as well as their independence make them complex animals and beg for analogies with human behaviour. Cats express our better and our worse selves. This part of the exhibition asks: how does modern Chinese brush-and-ink painters’ anthropomorphism of cat expressions merge with scientific-realist ways of picturing them?

The starting point is an undated hanging scroll painting by Cao Kejia 曹克家 (1907-79) and the older and more famous brush-and-ink painter Yu Fei’an 于非闇 (1888-1959). The painting’s composition is awkward. On the left two rootless stems of tiger lilies curve together in a heart shape. The flowers face each other. Yu claims in his inscription that they are after Qian Xuan 錢選 (c. 1235-before 1307), the Yuan-dynasty painter of pear and peach blossoms, autumnal grasses, and lotus leaves. But the painting belies Yu’s claim for the kind of meticulous pictures that made Qian famous: thick black contour lines and unmodulated oranges and greens flatten the lilies against the bare paper ground. These lilies are designed, not sketched from life.

In studied contrast, below the lilies, and looking up respectfully at them (a possible analogy for the relationship of the two painters), is Cao Kejia’s scientific-realist cat. It sits on its haunches, turned slightly away from the viewer (ignoring the butterfly floating above as well), thereby exposing the markings on its fur. It is a fuzzy, tactile fur, a fur rendered so that each brush stroke seems as if it is a combed on. The fur slides over the cat’s shoulder and rolls under its chin, and imparts a softness to the rounded line of its tail wrapped around its feet.

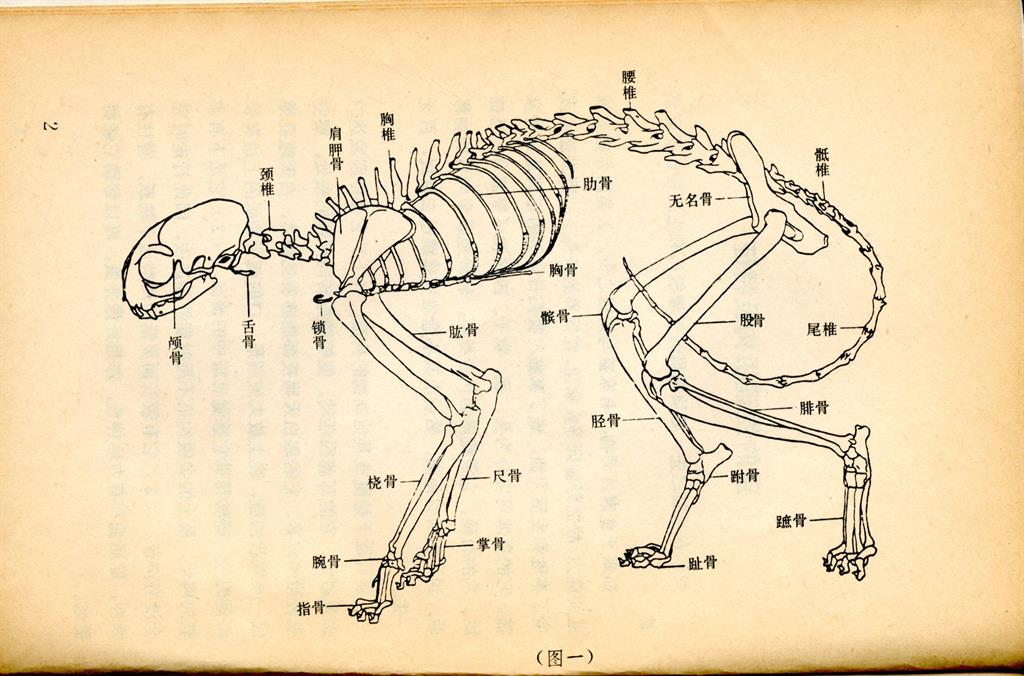

Cao was famous for painting cats -- so famous that in 1959 he wrote a painting manual entitledHow to paint a cat (Zenyang hua mao 怎樣畫貓).The first picture in it, featured in this exhibition, would be unexpected if it weren’t for the tangible immediacy of Cao’s painting style: it is a cat’s skeleton. Here “scientific realism” is revealed as deep knowledge of what can and can’t be seen with the naked eye when painting a cat. In the manual Cao connects the skeletal structure to special movements of cats, like capturing rats. Further, he says, to paint a cat depends first on getting its eyes right, and on knowing, even when painting the cat from behind, where its eyes would be looking and their position in the head.

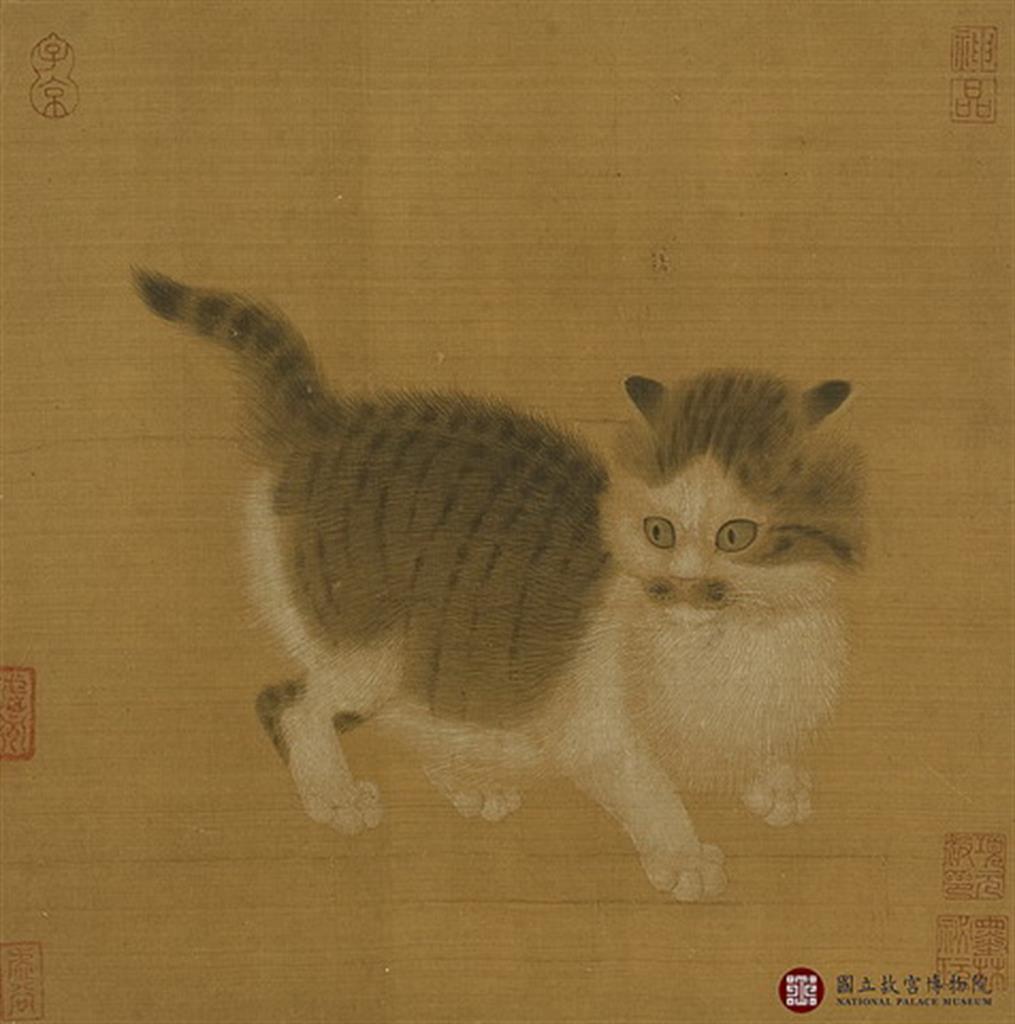

If the skeleton points towards anatomical study that is required of zoologists, another of Cao’s innovations that makes the cats look really real in his pictures becomes clear through a comparison of it with a kitten painted on silk, dating to the Song dynasty. The kitten is a striped dark gray colour, painted with washes and the thinnest of brushstrokes. As if about to pounce, its knobby white paws clench and its pupils contract. The delicacy and carefulness of the brushwork translate as skilled technique as much as softness of fur. Cao’s cat, in contrast, is painted with what he calls a “worn brush” (pobi 破筆), so that the textured surface of the fur composing the brush is translated into the textured fur of the cat on the paper ground. The hand making the mark disappears. Absenting his hand from his own brushwork is his innovation.

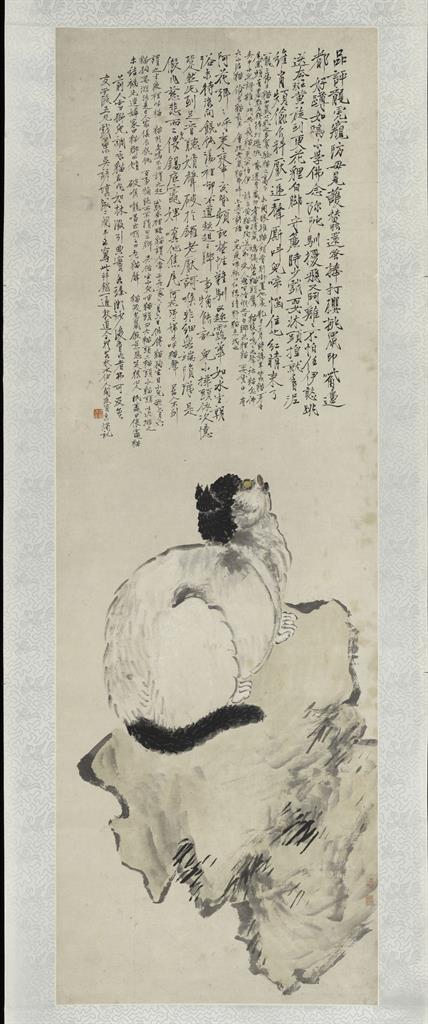

Other paintings in the exhibition comprise a collection of urban cats, half-feral cats, wartime cats, and maternal cats, and their expressions and personalities may be interpreted, in an anthropomorphizing vein, as expressions of each artist. The Shanghai painter Wang Li’s 王禮 (1813-79) unmitigatingly ugly cat, for instance, nonetheless fascinates for its sense of being caught just at a moment before it is about to leap. But then one wonders what it is to leap at? The cat perches on an unstable, floating rock which, as art historian Jonathan Hay observes, neither is identifiable as being part of a courtyard garden, nor is part of the artist’s built urban environment. It is a disembodied place (possibly connected to the uprootedness of many of Shanghai’s immigrant residents, among them the painter himself). And some of the crowdedness of the city is conveyed, as well. Though cat and rock are painted on a bare ground, that ground is made claustrophobic by the dense rain of inscriptions pouring down from above. The cat tilts its head to look up to them, as if the characters were a swarm of black insects grabbing its attention, or perhaps it is the case that the cat’s widening eyes are taking in the inscription itself, a catalogue of human behaviours for which cats serve as metaphors. “A heartless person crying false tears,” for example, “is ‘a cat who cries for a rat.”

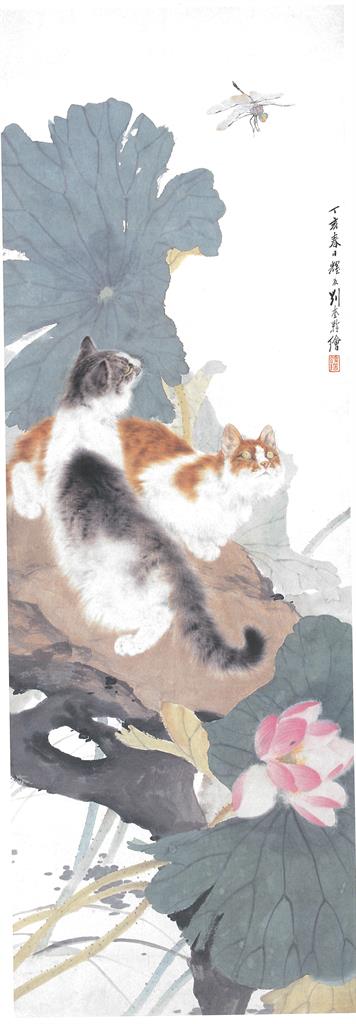

In contrast, Liu Kuiling’s 劉奎齡 (1885-1967) cats arguably are depicted in a real place, on a rock encircled by lotus in a garden pond. Still, where that pond is located is unclear. A public park? Wild nature? A courtyard garden? Liu was famous for his animal paintings, and especially for sets of hanging screen paintings that served as a kind of furniture for the home -- as habitat dioramas that complexly conjoined the space of a studio or main living room to the habitats of animals, wild and domestic. Liu raised cats and other animals in his courtyard home in Tianjin, did studies from life and museum specimens, and also painted from photographs he took of his own menagerie. He worked at bringing an “imaginative frequency” to the science of his brush. Whether or not these two cats numbered among his pets is not known, but the alert, crouched bodies of the cats as they watch a dragonfly – their companionship, and also their freedom -- speaks to the observational quality of his painting practice.

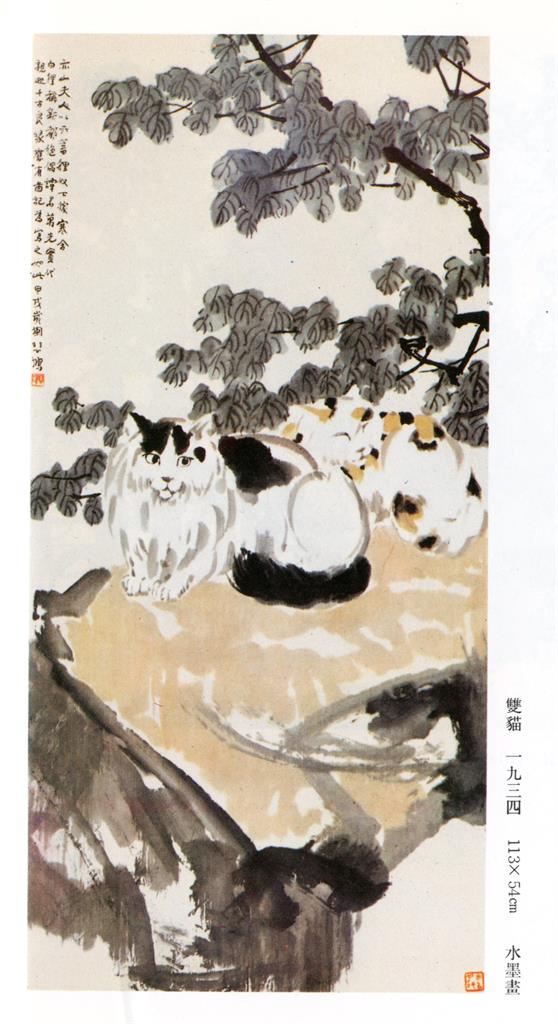

Wartime cats are represented in this exhibition by Xu Beihong’s 徐悲鴻(1895-1953) painting “Unconcerned” (manhan 顢頇). The almond-shaped eye of a black cat looking over its shoulder in pharaoh-like profile and the closed and upturned smiling eyes of the white cat at its feet convey the two diametrically opposed sides of feline personalities, haughty and friendly. The painter’s daughter Xu Fangfang translates the painting’s inscription: “Indifference is their best approach. To be muddleheaded is natural. They have been used to playing around since they were young. Extreme danger will not shock them.”Painted in 1934, the “extreme danger” Xu writes about is the political and social chaos making China vulnerable to the Japanese incursions leading to the second Sino-Japanese War in 1937 and to the wartime atrocities visited upon the residents of Nanjing, where Xu Beihong made his home. Around the time Xu produced this painting, he and his family cared for up to thirty stray cats.

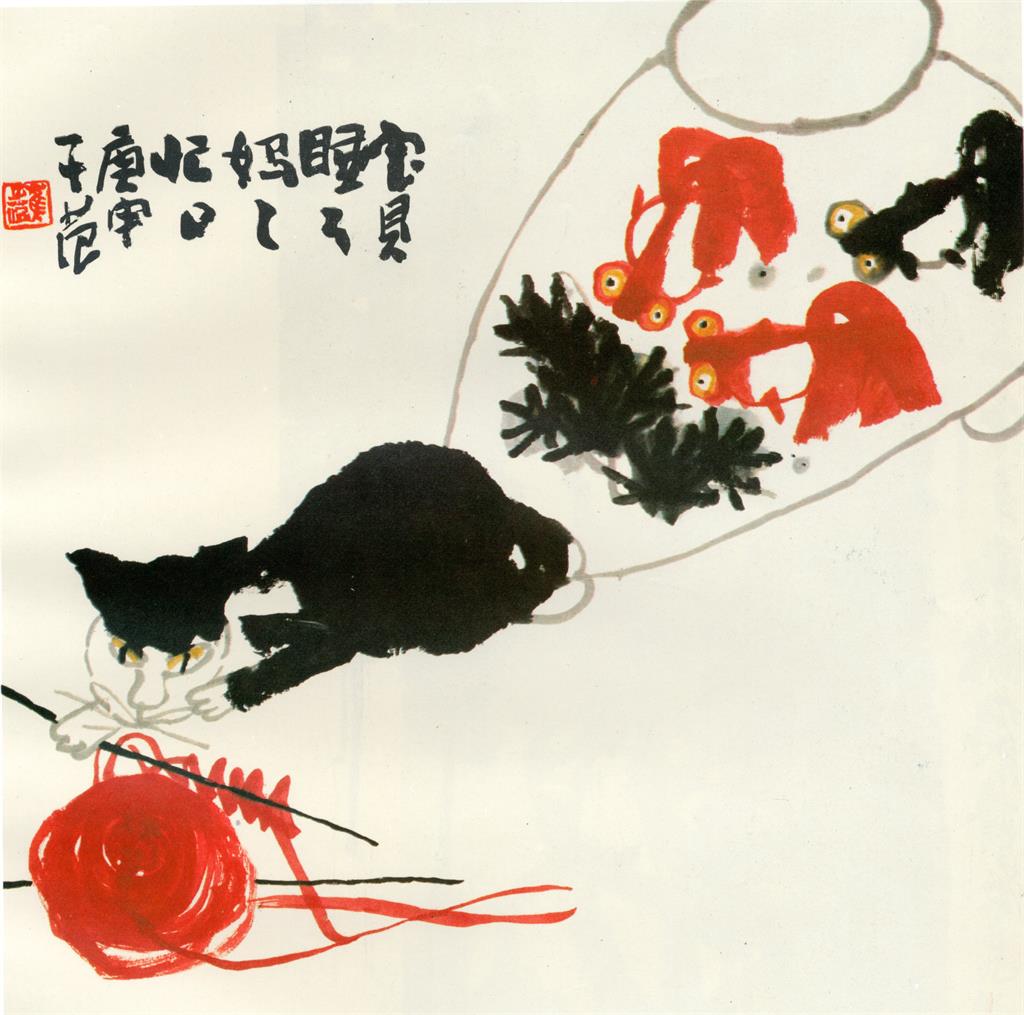

Cui Zifan’s 崔子范 (1915-2011) cat is a pictured as a maternal cat, a “busy mama” as the inscription puts it. Cui’s wet brush manages through only a few strokes to express the naughtiness of the cat as it attacks a red ball of knitting yarn while goldfish – the treasured babies of the inscription – look on goggle-eyed from behind. A subtle politics may float through Cui’s pairing of cat and treasure in the picture (one is reminded of former Premier Deng Xiaoping’s pragmatic aphorism that “It doesn’t matter if a cat is black or white [i.e., politically to the right or left]. As long as it catches mice, it is a good cat”). But Cui’s wry humour and gently awkward brushstrokes take the sting out of any political commentary.

Bibliography

Cao Kejia 曹克家. Zenyang huamao怎样画猫(How to paint a cat). Beijing: Renmin meishu chubanshe, 1980.

Claypool, Lisa. “Habitat Dioramas: The Animal Paintings of Liu Kuiling in Republican-era Tianjin,” Archives of Asian Art64, no. 2 (November 2014) [late]: 163-188.

Hay, Jonathan. “Painting and the Built Environment in Late-Nineteenth-Century Shanghai.” InChinese Art: Modern Expressions. Eds. Maxwell K. Hearn and Judith G. Smith, 77-93. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2001.