Essentialily

Curated by: Banafsheh Mohammadi and Justine Pelletier

This part of the exhibition places before you four images. Through its representations, this part attempts to explore what a lily is. Let us look attentively at each one and let us not settle for a momentary admiration. Let us attune ourselves to a state of hypersensitivity towards nature. I invite you to contemplate lilies with me.

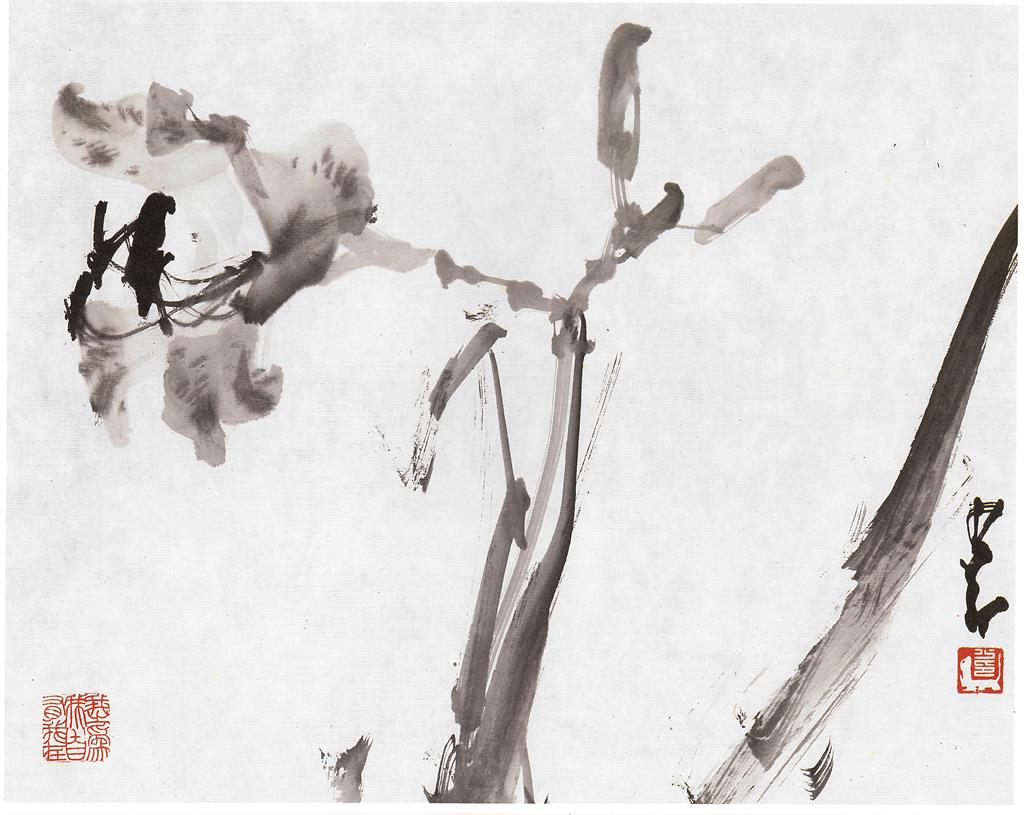

The main object in this exhibition is an untitled painting by Gao Jianfu (1879–1951) that depicts lilies. Look at these expressive lilies painted with dry, almost calligraphic brushstrokes. Each petal is drawn with a precise stroke showing us how elegantly it bends backwards. Opposed to these expressive petals are sharp stamens that seem to stand out from the flat surface of the scroll, almost pricking it and coming to life three dimensionally. The focus from stamens fades out into the nebulous leaves. This painting feels like a snapshot from a memory, a passage from clarity to obscurity. Look closely.

There are a few petals left on the lilies that you see on the upper part of the scroll. Do you feel the wind blowing? The wind might have taken the rest of the petals away. Are the absent petals a trace of the wind? Had I placed before you just a detail from this painting of lily flowers you could have instantly guessed that they are lilies, in fact, Turk Cap lilies. But could you have recognized the plant by the leaves alone? The leaves seem more abstract than the flowers. Again, there is a moving away from the focal point of flowers towards the periphery, to the leaves and the buds.

Compare Gao Jianfu’s lilies to Yun Shouping’s (1633-1690) lilies. Yun Shouping’s Tiger Lily seems more concrete. This lily seems to be well situated in reality, not in a memory nor in a dream. Six petals are meticulously painted as they bend backwards. Stamens stand out in full bloom and the leaves are just as exact as the petals. Pay attention to the change of color in the front and the back of the petals and leaves. Look how carefully dark specks have been placed on the petals. To the right of the lily, there is a lonely filament. Is it past its bloom?

The inscription in this painting reads: "Using mogu “boneless” technique, [I] deeply researched the sense of lifelikeness, washing off the trace of meticulous description and seeking to draw the spirit [of the flower], so that hopefully [I] would not go with the trend of the time [and] could wander beyond the appearance.”

Lilies, in imperial-era Chinese art, are often symbols of peace and harmony. Yun Shouping accompanied one of his paintings of lilies with a poem that reads: “How to make a peaceful courtyard? Plant this often. Loving its bright foliage is enough to forget worries" (Welch, 28). With this in mind take another look at his painting of lilies. Yun Shouping has contemplated lilies so long that he has reached a state of attunement with them; through his wet boneless brush strokes, lilies come to life. And this is no accident. He specifically wrote that by being able to paint the spirit of the lily he wandered beyond the appearance. If I ask what do these lilies ask of you when you gaze at them, what would your answer be? Could it be that the lilies invite the viewer to an affective state of harmony with nature?

Yun Shouping, one of the six masters of the early Qing dynasty who was famous for his flower paintings, is not disassociated from Gao Jianfu, as one might think. Gao Jianfu was a student of Ju Lian, who studied the works of Yun Shouping; through a generation, Gao Jianfu could be said to have been a student of Yun Shouping. But who was Gao Jianfu?

Gao Jianfu, the revolutionary Cantonese artist, was trained by the distinguished master Ju Lian for seven years. He, then, travelled to Japan in 1906 to continue his studies. It was in Japan, while studying entomology that he became involved with discussions over modernization and its impact on a country’s national identity. By learning entomology, for his style, Gao Jianfu adapted the scientific analysis of the object prior to depiction. This scientific way of carefully observing the specimen is what renders his paintings realist. After the revolution of 1911 he returned to China as a member of the revolutionary nationalist movement. With his brother, Gao Qifeng, and close friends from the south or “Lingnan,” Gao Jianfu tried to breathe a new life into the traditional Chinese painting. This was a moment in history, as the scholar of Chinese art, Eugene Wang testifies, that reforming Chinese paintings was a much contested topic of debate between traditionalists who argued for sketch conceptualism, and reformists who believed the same approach had degenerated Chinese paintings (Wang, 104).

Members of the Lingnan School were heavily influenced by Japanese art, but their artistic visions began to lose its popularity after the war with Japan in 1937. The Japanese romanticism of their paintings did not sate the social concerns of Chinese people anymore. In his classic study of Gao Jianfu and the Lingnan School, Ralph C. Croizier notes that the once revolutionary style of the 1910’s became outdated in the 1930’s and it failed to realize its national goal of bringing social reform – just as the once significant Canton faded into oblivion as it failed to keep its leadership over modern China. Gao Jianfu left for Macao in 1938 and only returned to Canton in 1945, after the Japanese were defeated.

The Lingnan School did not disappear altogether with Gao Jianfu. Zhao Shao’Ang (1905-1998) was a student of Gao Qifeng. He later became a key member of the second generation of the Lingnan School and garnered a reputation for his flower and bird paintings. Let us take a long look at his depiction of lilies. Chao Shao’an’s [Zhao Shao’Ang] three lilies are white. They have leaves whose dark green color fades as our eyes move upwards towards the top of the scroll, where we see the lilies hanging almost loosely. Compared to Gao Jianfu and Yun Shouping, Shao’an’s lilies have less pronounced filaments and stamens. There is another element in this image as well: a dragonfly. It is as if the artist’s expressive wet brushstrokes bleed onto the reality from a dream or a memory; the peculiar angle from which we see the lilies speaks to the dreamlike, uncanny context of the lilies. Your eyes wander through the painting. Can you trace Yun Shouping and Gao Jianfu in this painting? Can you see the meticulousness of the latter and the expressiveness of the former?

The relationship between Chao Shao’an and Yun Shouping can be traced through yet another analogy: the Lingnan school has a long tradition of adapting brush strokes and incorporating multiple styles for a painting. Long ago in the seventeenth century, Yun Shouping, after dedicating many years to the study of ancient paintings and contemplating nature, created his own particular style of painting which brought together “the polychrome style of professional artists and the ink monochrome style of scholar-painter” (Chung, i). The three paintings we have looked at so far sought to be more than an acute mimesis of reality. Could it be that they want to affect us, to elicit emotional reaction? Is it the essence of the lily, then, that bewilders us?

It seems as though wandering beyond the appearance and reaching the spirit of the flower, as Yun Shouping wrote, is a thread connecting the pieces in this mini-exhibition.

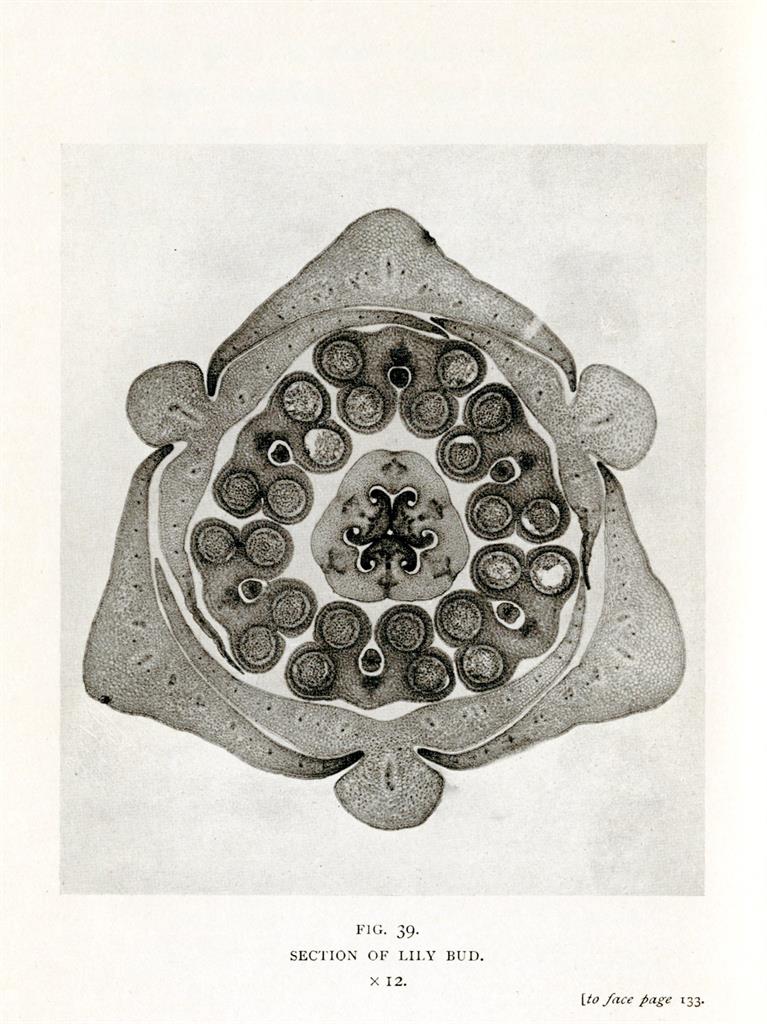

Let us, now, consider the other object in this exhibition: Observe the Section of a Lily Bud (1904) by Arthur E. Smith. This is a photograph taken by Arthur E. Smith and published in Nature Through Microscope and Camera by Richard Kerr. What we see in this photograph is a triangular shape, symmetrically permeated by three circular tendrils, which circulate around six other shapes. Think of Gao Jianfu’s Lilies. Can this photograph bordering scientific abstraction help us see Gao Jianfu’s Lilies differently? Are these six shapes representative of the six petals? There is a triangle in the middle with softened edges that seems to be a smaller scale of the overall shape. Do the filaments sprout from this core? The introduction to this book names biologists as the target readers. But this image seems to be more than just a scientific representation: this image is aesthetically appealing. Everything in this photograph is present in Gao Jianfu’s lilies. They exist as the a priori for the flower to be. Although taken by a camera under a microscope, which are after all scientific tools, Arthur Smith’s photograph intends to show us the symmetry and detail of a lily even when viewed on such a small scale: there is a design at every level. For the writers of the book, this revealed a divine presence. What does it communicate to you? Is the essence of the lily captured by the camera in a microscopic level? Is the essence to be found in the symmetry? Or is the essence omnipresent in the lily?

In this exhibition, you encountered many a manifestation of lilies. You looked at them and sought the aid of the artists to guide you with their words. But did you decide to settle for admiration? Let us think: think about what a lily is and in how many ways a lily can be demonstrated. Think about the essence of a lily and where it might be or even what it might mean. Are the artistic paintings at odds with the scientific photograph? Or do they complement one another? Think about where Yun Shouping wanted us to wander off to when we did not settle for the appearance with him. Think about your feelings when you saw each one of these paintings. Think about a scientific photograph that is aesthetically appealing and what it depicts is absently present in all other depictions of lilies. Now gaze at Gao Jianfu’s Lilies and let the wind carry you away to the realm these paintings have opened up for you.

Banafsheh Mohammadi

Bibliography

Chung, Saehyang P. “Yun Shouping (1633-1690) and the Orthodox Tradition of Chinese Bird-and-Flower Painting.” Ph.D. Dissertation, Columbia University, 1983.

Wang, Eugene. “Sketch conceptualism as modernist contingency.” In Chinese Art Modern Expressions. Eds. Maxwell Hearn and Judith G. Smith New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2001.

Welch, Patricia Bjaaland. Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery, 1st ed. North Clarendon: Tuttle Pub., 2008.