Kaleidographix

Curated by: Akosua Adasi and Daniel Walker

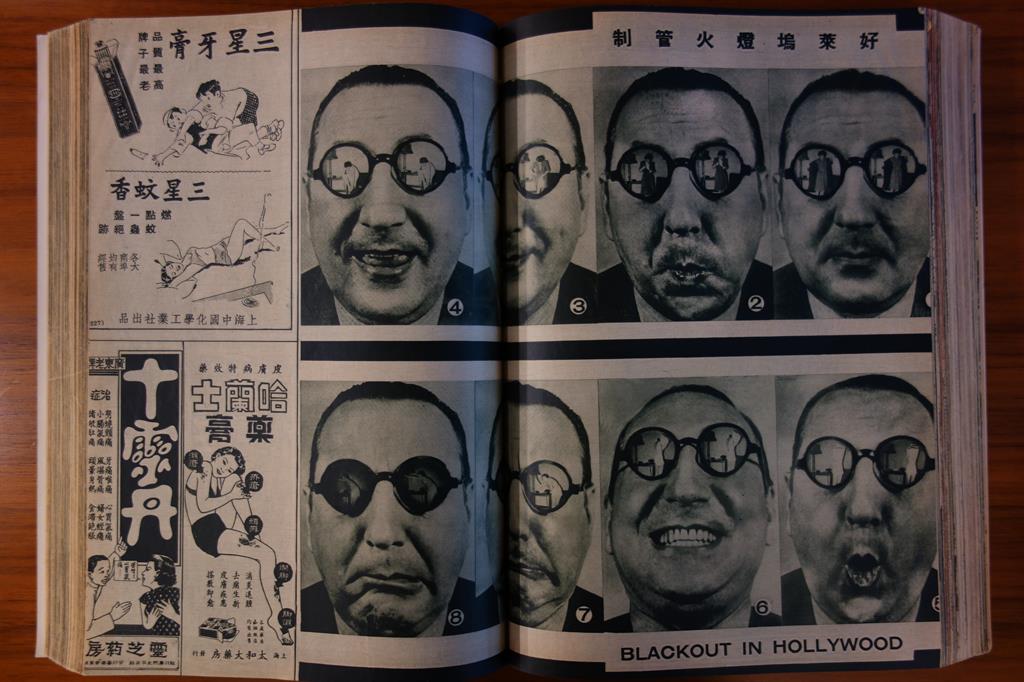

A 1940 issue of Liangyou [The Young Companion] features a striking image with the title “Blackout in Hollywood." Through layers of imagery in the composition we watch a man in eight separate frames, peering at a woman as she undresses, frame by frame, in front of his eyes. In this series of photographs we do not see through the man’s eyes. Instead, our gaze intersects with his own in the lenses of his glasses—which are as if transformed into a movie screen—allowing us a privileged vantage point from which we look at himwatching her. The man’s cinematic view does not last long, though. The screen on his glasses abruptly blacks out, blocking his desiring gaze, as well as our own, in the process.

This type of fragmented imagery is not so unusual in Republican-era print culture in Shanghai. The practice of representing modernity as visually kaleidoscopic, about spiraling and expanding processes of looking, marks the jazz-hot modern years from the collapse of the last dynasty in 1911 to the establishment of the People’s Republic in 1949. In this section of “Making the World,” we dwell on sight itself, focusing on the gaze directed towards women, with an eye to how their kaleidoscopic quality fed the construction of a new “vernacular sociology”—informalized studies of the common social practices and thought of urban, middle-class populations.

In the early 1930s and 1940s, China’s new foreign-trained sociologists were turning to an examination of the country’s people and places with attempts at establishing the social sciences in China. Concurrently, print culture—representing rapidly modernizing city space—targeted China’s new urban dwellers with luscious periodicals that were highly designed to entice the eye. The demand for print culture skyrocketed at this moment, and many periodicals focused on the Shanghai urbanite, be it through consumption patterns, leisure activities, or political engagements. Turning to the everyday life of Shanghai’s educated consumer class thus trained the eye to see a new kind of vernacular social sphere that emerged within this seductive moment in Shanghai’s development, one marked by social re-coding, political instability, and the spoils of modernity.

Vernacular sociology emerged from the cracks of institutional practices, according to cultural historian Tani Barlow, just as those practices themselves were being re-molding during China’s Republican period. The social sciences underwent professionalization within broader contexts of vernacular thinking about twentieth-century China. Vernacular thinking—looking to the everyday practices of Shanghai’s middle classes—revealed transformative changes in social life. These changes required a new type of vision that embodied the kaleidoscope in order to grasp the breadth of fast-paced changes that were remolding urban life in Shanghai. In this environment, vernacular sociology emerged, independently of the social sciences of the academy, as cosmopolitan men and women engaged with social theories. Shanghai’s veritable melting pot of cultures and consumer pleasures was a ripe avenue for experimentation with social theories, these ideas being disseminated in “journals of the enlightened opinion” (Barlow, 319), which were “looser [and] less focused on professionalizing the social sciences” (Ibid). Rather than concerned with professionalization, these journals spoke to the cultivated city-dweller who was reading newly translated works available for the first time in China. Nourished by these texts, journals that helped shape vernacular sociology focused on racial improvements, national strength, enlightened social thought, and the question of women’s empowerment.

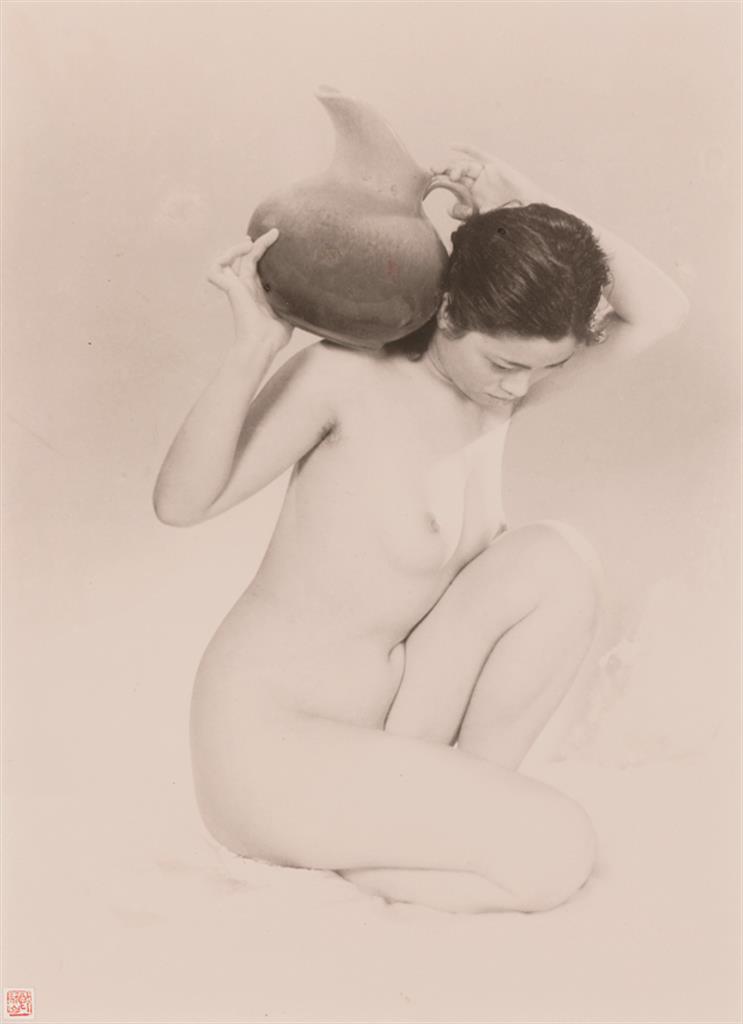

Pictures of women were a core focus of vernacular sociology. Philosophical interests in female liberation and subjectivity, as well as thinking about women as both outcomes of natural and social evolution, helped locate the female body within this discourse. In this sense, vernacular sociology contributed to developments in modern subjectivity among Shanghai’s city-dwellers. Popular magazines, by contributing to the development of vernacular sociology, “structured modernists’ foundational understanding of personality, social reality, historical processes, the role of natural processes and natural science in social relationships and institutions” (Ibid, 323). Within this exploration of theoretical activity, the woman placed at the center of vernacular sociology was one that served as an icon of progress. This woman—represented in photography and advertising—was associated with “sociological platitudes about women’s perfectibility with her biological-scientific body” (Ibid, 332). It is precisely from the fertile intellectual playground of cosmopolitan Shanghai that the female body was seen as infinitely more than herself. Rooted in image-form in the period’s print media, she consumedall the spoils of consumer capitalism and was consumedas an image of national health and social development. An effect of vernacular sociology’s exploration of social theory, the modern woman represented in print culture shone as an ideal form of scientific, modern womanhood.

In an image from World Peace News Service we are introduced to an enigmatic use of the eye, one that incorporates vernacular city space into the male Japanese subject’s own sight. This image, printed in Shidai Manhua 时代漫画 [Modern Sketch], suggests an emphasis on looking through the replacement of eyes with external images. The eye is sliced out of the image and expanded through the integration of urban space in its place. While the man’s eyes expand out, his body disappears on the page. Male sight, here, is privileged over the body. This is further reinforced through the presence of the man’s lipstick-red lips—feminizing what is visible of his form—and undercutting the authority of his presence.

Both “The Parcel Goods” and a photograph of a female nude by Lang Jinshan 郎靜山 locate the female body at the center of our gaze. Unlike the previous image, which points to new modes of vernacular sight through the invasion of the eye with kaleidoscopic imagery of city life, the female body commands our attention through its presence on the page. Lang’s photograph molds the model’s pose to approximate that of the vase she holds in her hand. Doing so aligns the woman’s body with the object she holds. Further emphasizing the relationship between commodities and the female body, in “The Parcel Goods,” the body metamorphoses into a consumer object right in front of our eyes. This transition pushes us to consider the image as it is can be read alongside developments in vernacular sociology. In muddying the distinction between consumer commodity and body, the figure in the image expands outwards kaleidoscopically, her body becoming emblematic of consumption as well as feminine ideals.

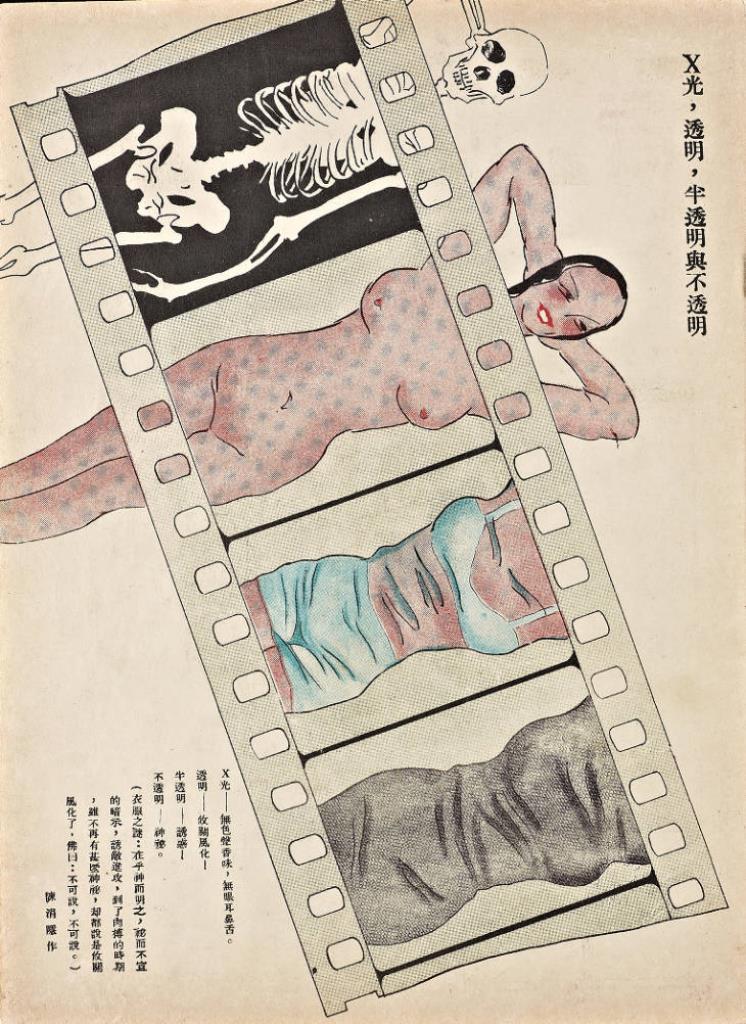

If “Blackout in Hollywood” scrutinizes the female body, so does Chen Juanyin’s Modern Sketch illustration "X-ray, Transparent, Semi-transparent, Opaque." On the one hand, both “Blackout” and “X-ray” transform the female body into objects to be looked at by the desiring male gaze, seen specifically through the implied Hollywood camera and the x-ray. Rather than simply pornographic, the framing of these images through the camera and the x-ray turn to the female body as sites of technological scrutiny. This bodily scrutiny emerged in part through the influence of vernacular sociology, suggesting the body’s privileged position as a malleable cultural product within explorations into female health and scientific ideals. As designers of popular magazines conflated images of female beauty with ideals of national health and the flourishing of the nation, the female form—unlike its male counterpart—was rigorously examined and placed at center stage as a promoter of a stronger nation.

Liangyou and other magazines were not only parsed for glimpses into China’s consumer pleasures, but were also sites that contributed to a developing vernacular sociology. It is thus not uncommon to for images of the female body to be emphasized in print media. That these images helped craft new modes of femininity that “[passed] the scrutiny of the “scientific gaze” and contributed to the progress of the “modern nation”” (Pickowicz, et. al., 8) is a testament to the fluidity of media images during this ever-shifting period. While China’s first sociologists were busy developing sociology in the academy, the popular press was in embrace of a kaleidoscopic visuality that helped craft a distinct form of scientistic knowledge—verging on science, referencing science, implying science—but not the same thing as the science of the academy. In a society actively shaping its present and future, vernacular sociology emerged as a symptom of modernization in print culture, which was at work representing all that it saw in the modern world.

Bibliography

Barlow, Tani E. “Wanting Some: Commodity Desire and the Eugenic Modern Girl.” InWomen in China: The Republican Period in Historical Perspective, edited by Mechthild Leutner and Nicola Spakowski, 312-350. Münster: Lit, 2005.

Pickowicz, Paul G., Kuiyi Shen, and Yingjin Zhang.“Liangyou, Popular Print Media, and Visual Culture in Republican Shanghai.” In Liangyou: Kaleidoscopic Modernity and the Shanghai Global Metropolis, 1926-1945, edited by Paul G. Pickowicz et al., 1-13. Leiden: Brill, 2013.