Bird’s Eye Views

Curated by: Anran Tu and Liuba Gonzalez De Armas

The idiom “bird’s eye view” denotes an imagined perspective in the human visual experience of seeing. The term is defined in the Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms as “a scene…depicted from an imaginary viewpoint high up so as to give a comprehensive overview.” Adopting the idiom and its imagined experience of being a bird, this section features the look of birds’ eyes and optical activities of birds in paintings, illustrations, and specimens, where we are invited both to look at and look through the bird’s eye. This time we are not looking down at the landscape as birds in the sky, though. We will take up different subject positions which are defined by our visual relationship with the represented bird, that is, how the bird and its eyes look, how we look at them and are looked at by them. It is in this intensified network of looking that meanings, values, and our ontological relation to the bird were incubated, hatched, and matured.

This section explores different representations of birds’ eyes in various cultural conventions, geographical regions, periods, and for different purposes. By seeing and contemplating the visions of a bird’s eye, we ask, how does the bird’s act of looking (or not looking) affect the way we look at them? How does the depiction of the bird’s eye and the optical activity of the bird mediate the beholder’s visual experience, and thus reveal the function and purpose of the representation? The theme of this section is, ultimately, the reflection of our subjectivity in the eye of birds, taking up John Berger’s curious observation that an animal “does not reserve a special look for man…but by no other species except man will the animal’s look be recognized as familiar.” The look of the animal attributes a uniqueness to them as the Others of human, which demarcate, confirm or challenge the boundary of man’s Self, which is an experience unique to modern man. What, then, could these different ways of rendering bird’s eye vision suggest about the relationship between man and birds in the historical moment when the object was produced?

Our central objects are two paintings of imperial China from the Mactaggart Art Collection at the University of Alberta. The first, a goose, depicted by the early Qing artist Zhang Chong (1502-1579), is improvised (manxing 漫興) in a free, expressive style, with elegant brush traces and light washes rendering the goose and the landscape in a simplified manner. The goose’s eye, interestingly depicted as a half-circle with eyeball nearly protruding out, highlights the attentiveness of the bird staring at the distance. The eye of the goose manifests a psychological intensity that is comparable to that of a man. Zhang’s anthropomorphic goose exemplifies the artistic rhetoric of Chinese scholar-official artists, which placed weight on the expression of self over the objective natural world. Zhang’s goose, with a caricaturistic, human-like staring eye, is at once the incarnation of the artists’ inner world and the interior view of the world. While observing and depicting the birds, the subjectivity of the artist and the bird became one.

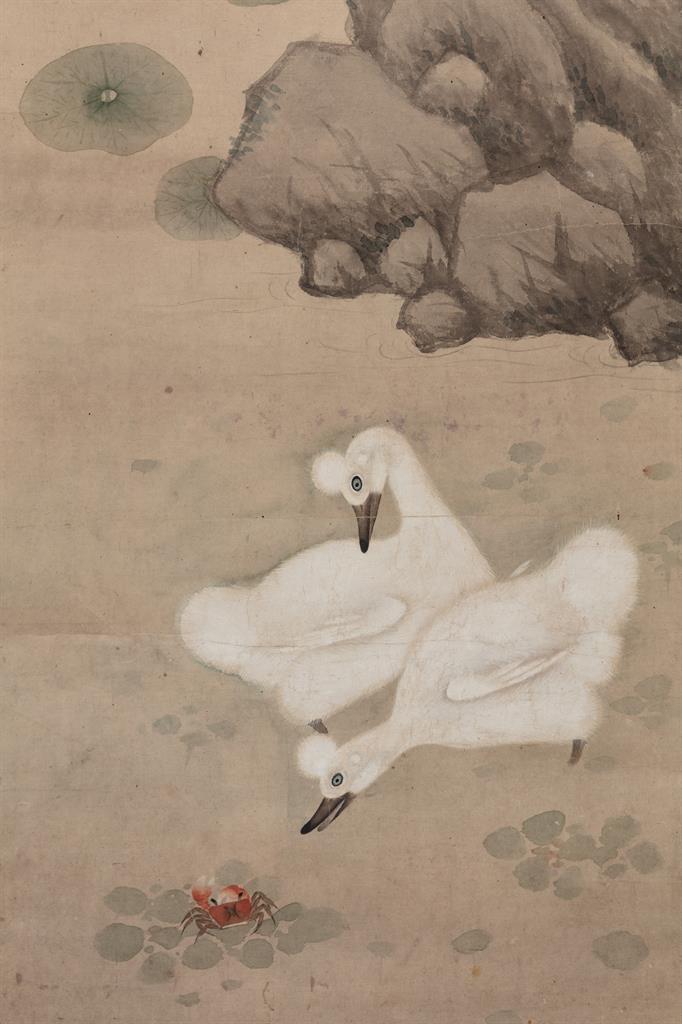

Different from the “improvised” goose in Zhang’s painting, the second work from the Mactaggart Art Collection on display, by Li Yuankai (17thcentury), represents a different tradition of Chinese art, which portrays nature in a more meticulous, refined, almost self-effacing style. The eyes of the pair of ducks in Li’s painting function less as a merging point of the bird and the artist’s subjectivity, and more as a focalizer in the pictorial composition. The ducks’ look at the crab on the duckweed draws our gazes in the same direction. In doing so, they highlight the rebus of the painting: the auspicious message of marriage and giving birth (explained in the painting’s individual label).

But this is not the entire story of the ducks in Li’s painting. The work serves as visual evidence for modern scholars of the existence of a historical breed that has been lost for three hundred years. In 2013, farm animal specialist and breeder Shen Xiaokun and his team in Zhenjiang, China successfully produced the "Black-beak white crowned duck," bringing back to life this lost breed. This section proudly features his photograph and the story of the breed of duck as companions to Li’s painting.

Still, the slippage between rebus and meticulously rendered painting raises the question of what defines our vision of an “accurate” representation of a bird. The comparative anatomical illustration of Central Nervous System of Birds (1854) by Nicolas Henri Jacob (1782-1871) fleshes out one possible answer, which shows the correct structure of the visual system of different birds. This illustration exemplifies a burgeoning mid-19thcentury academic inquiry into the difference in the anatomical structure between man and different animal species, which was part of a growing interest in comparative anatomy and the establishment of ornithology in the eighteenth and the nineteenth century. Vision plays a centralized role in this process of distancing the observing subjects from the observed objects, a paradox that Berger describes as “the familiar look” that man was searching for in animals’ eyes.

John James Audubon’s illustration from the Birds of America (1838) featured in this section anticipates this trend: how would a bird “look” in a painting produced by an artist who was increasingly aware of himself as an observer? The lifelike, violent scene of two hawks mercilessly tearing apart their prey is kept at a safe distance from the viewer by the pictorial frame. Contrasting to the birds’ eyes represented in Zhang’s and Li’s paintings, the eyes of the hawks are rendered naturalistically yet are nearly indifferent and emotionless, and they convey none of the violence and aggressiveness of the activity in which they were engaged. Despite the naturalistic style of the artist, Audubon’s hawks are undoubtedly closer to bird specimensthan Li’s ducks.

By that, we mean that Audubon painted his birds based on what he hunted in the field or on dead specimens that he pinned into positions in which he wanted to paint. In China, it was not until the early twentieth century that the practice of painting birds based on specimens was well documented in the writings and drawings of Chinese artists. The painting of the yellow-browed bunting in this exhibition, originally depicted by Chinese artist Jin Cheng (1878-1926) and copied by his disciple Yang Min (杨敏) for publication in art journal Hushe yuekan 湖社月刊, demonstrates the process by which a “bird-and-flower” painting came from a bird specimen. When Chinese artists began to adopt the practice of depicting specimens, the bird’s vision dimmed: their eyes were no longer an incarnation of a human soul, or part of intricate plays between naturalism and symbolism, and instead became no more than a glassy surface reflecting our observing gaze. As such, the bird illustrations in the Hushe yuekandeclares their modern “scientific” quality while the medium and the respect for Chinese pictorial tradition persisted.

A specimen is also a form of representation. The bird’s eye in any specimen is the only visible part of the bird that did not belong its original body. Writer and curator Rachel Poliquin succinctly described the process of specimen preparation in the seventeenth century (which still applies today): “After being skinned, birds were cut in half longitudinally. One half was filled with plaster ... An eye was inserted, and the actual beak and claws of the bird were used or represented with paint.” A specimen of harlequin duck from the University of Alberta Ornithology Collection shows the absence of eyes and cotton stuffing through the eye socket. Without the eye, the specimen appears to be much less “lifelike” as a legible representation of a real bird; it was reduced to an object, or a dead, artificial thing.

Does art map our distance from animals and our central place in the natural world, as science does? Or could art challenge the boundary between animal and human, in a world where the alienation and exploitation of nature by modern industrial powers is undergoing fierce criticism? Our little history of the visual representation of bird’s eye in this section would not be sufficient to provide a comprehensive answer to these questions. In the world where man and animal are clearly and “scientifically” separated, the experience of a seeing bird would be alien to us. It is not our intention to call for a nostalgic return to a premodern utopia in which we can see a goose standing at the shore attentive gazing the distance, like a contemplating human. Yet it is our hope in this section to provoke further contemplation on our relationship to natural beings mediated by both art and science.

Anran Tu

Bibliography

Berger, John. Why Look at Animals? London: Penguin, 2009.

Clarke, Michael and Clarke, Deborah. The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms. 2nd Edition. Oxford University Press, 2010.

Crary, Jonathan. Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1990.

Hushe yuekan 湖社月刊 [Heshe Art Magazine]. Tianjin: Tianjin guji shujian, 1927-1936.

Poliquin, Rachel. The Breathless Zoo: Taxidermy and the Cultures of Longing. University Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2012.

Roberts, Jennifer. Transporting Visions: The Movement of Images in Early America.Berkeley, Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2014.

Sowerby, Arthur de Carle. Fur and Feather in North China. Tientsin, North China: Tientsin Press, 1914.

Sung, Hou-mei. Decoded Messages: The Symbolic Language of Chinese Animal Painting. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

![Goose [untitled].](/apix/Items/Image/51?guid=90fdd7b7d4f048cf9764e723798a454f&size=Large)

![Central Nervous System of Birds [untitled]](/apix/Items/Image/57?guid=54157d820a7247999bedccc17979a7f8&size=Large)