Lepidop-eternity

Curated by: Julie Dranitsaris and Chelsea Jungeon Koo

How can the short-lived but febrile energy and the fragile scales of butterfly wings be captured in pictures?

This part of the exhibition begins with butterflies flitting and swirling to us from the distant past through the gouache and ink-painted pictures on watermarked pages of a bound album once owned by Sir Thomas Phillipps (1792-1872). A self-styled “vello-maniac” and a connoisseur of books, he carefully inscribed an inner title page with the words “Chinese Drawings: A collection of 30 very beautiful and delicately coloured Drawings of Butterflies and other Insects, Plants, Shrubs, etc. By Chinese artists.” Inside, a pea-pod-green mantis raises a raptorial leg above its shadow; a transparently blue-gray winged butterfly hovers above a white hibiscus; moths, grasshoppers, wasps, cicadas, spiders, dragonflies and seed bugs, among the insects painted life-size on the bare ground of the pages, haphazardly compose Phillipps’ visual “et cetera.”

This album, and others like it, were painted by anonymous hands in the southern port of Canton (Guangzhou City) before the earnest empire-building British launched the first of the devastating Opium Wars that opened China to trade, and enabled the explorations of naturalists inland. This album was made at a moment, in other words, when travel of foreigners in China was restricted. Partly hence, European knowledge of what China’s insects looked like was limited by distance and a circumscribed variety of specimens; pictures initially stood in for the real thing.

And yet, these pictures failed as specimens. Such failure cannot be put down to the feather-fine brushstrokes delineating antennae and eyespots on wings. Equally, it cannot be put down to a sometimes uneven quality to the painting -- so that on one page a pale blue butterfly may be rendered immaculately, while on another, the same butterfly, in the same hovering position, loses definition and instead sparkles with powdery mica and impressionistic colour. It cannot be put down to a kind of cross-medial migration of butterfly from embroidered silk robes to album paper and back. Neither is the status of the pictures called into question by the style-driven travel to and from the paintings of the local Cantonese artist Ju Lian 居廉 (1828-1904), who studied insects with a naked eye and obsessively painted them in his Ten Fragrances Garden (Shixiang yuan). (A nineteenth-century embroidered robe and a painting by Ju Lian are featured in this exhibition).

Instead, the failure is pointed to by a drawer of butterfly specimens in the University of Alberta E.H. Strickland Entomological Museum. Unlike the album paintings there is order to the bodies of the butterflies on display. Their spacing and wing position impart uniformity. Yet, even though so obviously different in composition to the album, something else here signals the pictures’ failure, and that final determiner of failure is paradoxically invisible to the eye. Beneath the iridescent blue-green wings in the drawer are labels in tiny micrographic script, pinned to the insects’ thoraces. It is writing – naming -- that turns insect into specimen.

Writing is conspicuously absent in Sir Phillipps’ album. Still, there remains something stubbornly specimen-like about these pictures, and we may wonder why. How is the ephemerality of the insect lodged in the picture? How do they attain lepidop-eternity?

A painting on silk of a butterfly and hibiscus by the brush-and-ink painter Qi Baishi 齊白石 (1864-1957) dating to the late nineteenth century, just when he was learning to use his ink brush, illuminates a long cultural history to picturing insects with a kind of scientific realism, a beginning of sorts to lepidop-ternity. The painting features a butterfly hovering above a pink hibiscus flower. Half rendered in boneless wash, half with heavy black contour lines, the butterfly and plant curve towards each other. To the left, Qi has written his studio name “Old Man Duckweed” (Ping weng 萍翁) in a distinctive style of lacquer-script calligraphy – not his own style, in fact, but that of the eighteenth-century painter Jin Nong 金農 (1687-1764). Jin was active during an era of epigraphic study, a time of cultural search for origins, for seriality, for lineage. This was an era of slow looking for the authentic trace – the kind of exacting gaze that came to characterize the entomological eye. His calligraphy style draws explicitly from immersion in epigraphic form.

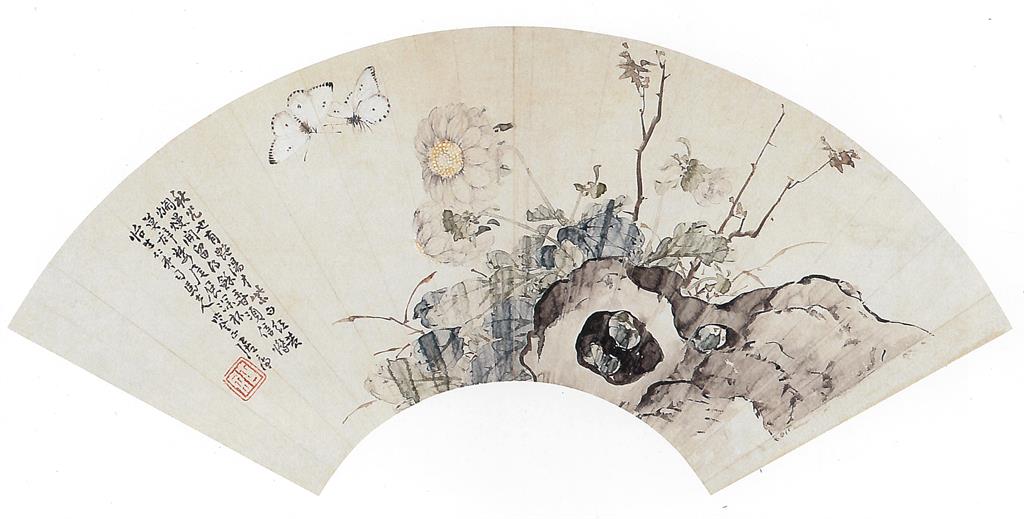

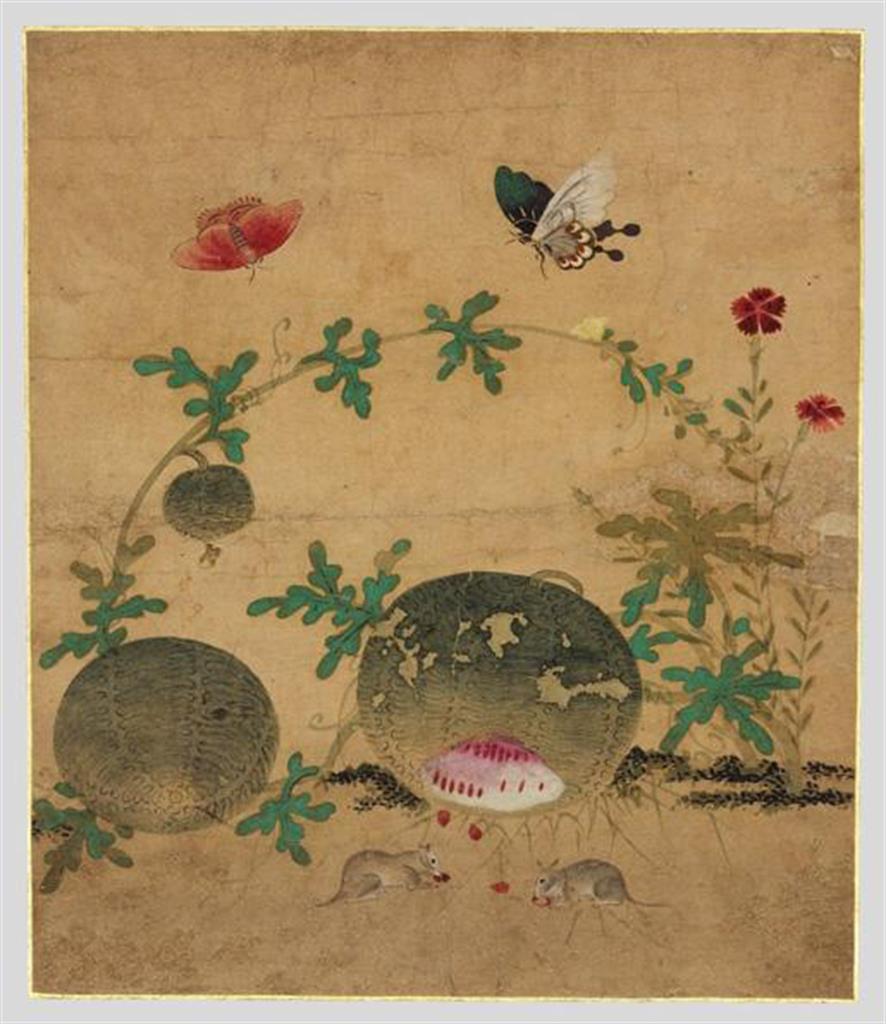

If the script style makes claims, rhetorical in nature, for an intent gaze at the wings of a real butterfly, the pictures themselves may point in a different direction. There is something diagrammatic and template-like about flower and insect, a kind of grammar of form that would one day serve as insect illustration in entomological dictionaries and popular textbooks. In this case, though, the source is not a scientific tome, but most likely is a page from the famous Mustard Seed Garden Painting Manual (Jieziyuan huazhuan 芥子園畫傳) that much later, after Qi had achieved fame and international recognition, he said he had studied in his youth. Complicating this story of seeing and making is another painting practice, possibly a gendered practice, and it is one that crosses dynastic time and culture even more broadly writ. The final two paintings in this part of the exhibition make this point. The first a handscroll by Ma Quan 馬荃 (act. early 18th c.), a “woman scholar,” as she called herself, active in southcentral Jiangnan during the century before the album paintings were made. The second is a flower and insect composition from a set of eight by Sin Saimdang 신사임당 (1504-51), a Korean painter active in the sixteenth century who may have responded with her brush, possibly as Ma Quan did, to ancient Chinese Song-dynasty (960-1279) paintings in the piling 毗陵style, named after its place of origin (modern-day Changzhou), also in the Jiangnan region. The style is distinctive in the main for its for its delicately modulated brushstrokes and a compositional formula of a central clump of flowering plants with balancing elements on either side. To begin with the earlier artist: Sin Saimdang studied painting from her youth, starting with the paintings of An Kyon 안견 (1418-?), who counted among his patrons the Prince An-p’yong 안평대군 (1418-53), the owner of a large collection of Chinese paintings of the Tang, Song, and Yuan dynasties. Her picture featured in this part of the exhibition is anchored by a heavy melon at its centre, its pink flesh and seeds exposed by nibbling mice below; on the left, the mineral green lobed leaves and stem of the melon plant take the eye up and over to hovering butterflies; on the right deep red flowers connect to the fleshy colour of the melon below, completing the compositional circle. Ma Quan’s handscroll painting is strikingly different. Its composition is determined by the format of the handscroll that unrolls from right to left. Each cluster of butterflies creates its own circular cell of space, though these also are threaded together by a kind of modularity of form. The painting’s design sensibility – the repeated shapes and colours -- draws it closer to the embroidered butterflies on the court robe in this exhibition. And yet the butterflies float over the silk just as the detail skims along its surface, and in this way Ma Quan’s painting also is reminiscent of Song-dynasty piling-style paintings. Lisa Claypool