Mapping Motion

Curated by: Connor MacDonald and Yue Wang

Nineteenth-century China was convulsed with warfare and rebellion. Among the conflicts was the Nian Rebellion.Largely in response to local famine caused by flooding of the Yellow River, the Nian outlaw bands overran provinces in central and northern China, causing chaos for fifteen years (c. 1853-1868). Yet at the time and later, in histories, the Nian Rebellion has been over-shadowed by the concurrent mid-century Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864), for unlike the Nians, the Taiping rebels possessed a strong central leadership and an articulated political ideology. Nonetheless, for the Qing court, the victory against the Nians was hard won. To commemorate their success in suppressing this prolonged insurrection, a set of eighteen large-scale paintingsof the various battles launched against the Nian rebels—a court painting workshop project probably directed by the brush-and-ink painter Qingkuan 慶寬 (1848-1927)—were commissioned by the Guangxu emperor 光緒 (r. 1871-1908) and produced during the mid-1880s, including the central painting on display in this part of the exhibition.

The composition of the Battle Scene of Nian Rebellionis artful and cartographic in its visual references. Rebels in the immediate foreground and war refugees in the far distance move against the right-to-left advancement of an overwhelming number of Qing soldiers on foot and on horseback. The orderly and confident approach of the imperial army contrasts with the helter-skelter fleeing rebels. Yet very little blood is let; the violence is contained to a few sprawling rebel bodies encircled by Qing military banners in regimented formation. Even the horses surge forward as if one body. The tidiness of the pacification is amplified by its context: a serene landscape with endless mountains, blooming trees and well-tended houses. It is as if the orderly movement of the army is symbolically connected to the pristine land and pastoral villages. And yet the pathos of the war refugees exiting their village figures as a kind of visual disturbance in the composition; it encourages viewers to contemplatenot only the artful ideological but also the real physical context in which the battle took place.

The commission of this set of battle paintings in the 1880s by the Guangxu emperor 光緒 (r. 1875-1908) was not coincidental; it emulated a similar project commissioned by his great grandfather, the emperor Qianlong 乾隆 (r. 1736-1795), over a century earlier. Emperor Qianlong, who proudly called himself “The Old Man with Ten Achievements” (Shiquan laoren 十全老人) for having won ten major victories in the wars of conquest, ordered a number of folios of copperplate prints to be made of “The Conquest of Western Regions” (Pingding xiyu zhantu 平定西域戰圖), also called “The battle-pieces of the conquest of Dzungaria and Chinese Turkestan” (Pingding zhun Hui liangbu deshengtu 平定準回兩部勝圖). Aseries of sixteen black and white copperplate prints (two fewer pictures than the later Nian series of paintings) were produced for the emperor in the mid eighteenth century in Paris under the direction of Charles-Nicholas Cochin (1715-1790), from sketches made by Giuseppe Castiglione (1688–1766) and three other European Jesuits who served at the Qing imperial court that had traveled the globe from China to France through the support of merchants in southern China.

Among the sixteen engraved pictures (to which the Qianlong emperor added poems and encomia), Storming of the Camp at Gädän-Olaby Castiglione closely resembles the Battle Scene of Nian Rebellionfor the way it renders motion and stasis. Characterized by intense action and drama, the battle scenes portray sometimes brutal fighting between the pursuers and the pursued, as well as the dead, the wounded, and the runaways. While the proscenium-like composition of landscapes holds viewers’ attention still as if everything revealed to the eye is staged – as if a tableau out of time -- the troops’ flowing movementin those landscapes encourages viewers to move with them -- to be transported to the rugged battlefields to relive the horror and excitement of the battle.

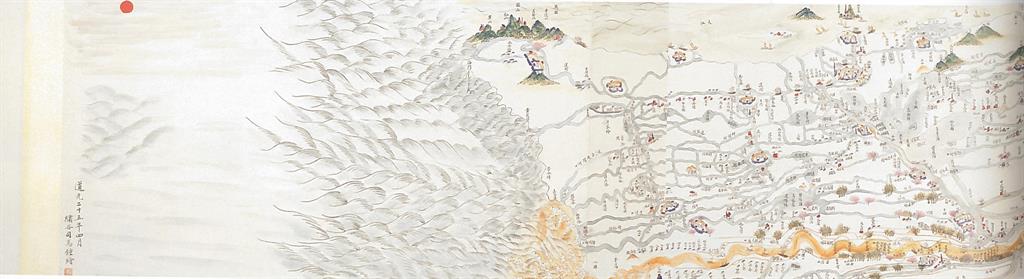

One major difference between the Storming of the Camp at Gädän-Ola and the Battle Scene of Nian Rebellion is scale. The painting is significantly larger than the print and its size allows it to function similarly to a handscroll —a long narrow scroll of pieces of silk or sheets of paper on which a scene has been painted horizontally in a continuous fashion, and which, when not being viewed, remains rolled up for storage (see, for instance, theMap of the Yellow River, also featured in this part of the exhibition). Handscroll paintings are meant to be handled and touched. As the narrative progresses – it unfurls as the scroll is unrolled right to left -- viewers might find themselves imaginatively entering into the depicted space, pausing, moving on and sometimes going back. The experience of viewing a handscroll painting has been analogized to watching a movie: each newly unrolled section presents an expanding scene. In this way, looking at a handscroll is very much similar to visualizing the Battle Scene of Nian Rebellion: just as one unrolls a handscroll, not knowing what to expect, viewers’ eyes move from section to section over the large expanse of silk ground in the battle painting. In both cases, in order to delve into the narrative depicted in the painting, one must only gaze at a particular space cell within the entire expanse of the painting.

But such vascular connections to print compositions and the scroll painting formats also can be found in maps. Unlike maps today that implicitly tend to emphasize the value of scientific accuracy through mathematically determined scale and spatial relationships, imperial-era Chinese maps were typically more “descriptive”—that is, less like abstract grids and more on-the-ground. For example, the painted Map of the Yellow Riverimmerses the viewers inmountains and rivers as they would be seen from the point of view of a traveler moving from the west to the mouth of the river in the east, where it spills into the Bohai sea. That means that sometimes villages spin sideways through space; groves of trees appear as big as mountains; mountains in the far distance are ghostly gray washes, as if just beyond sight.

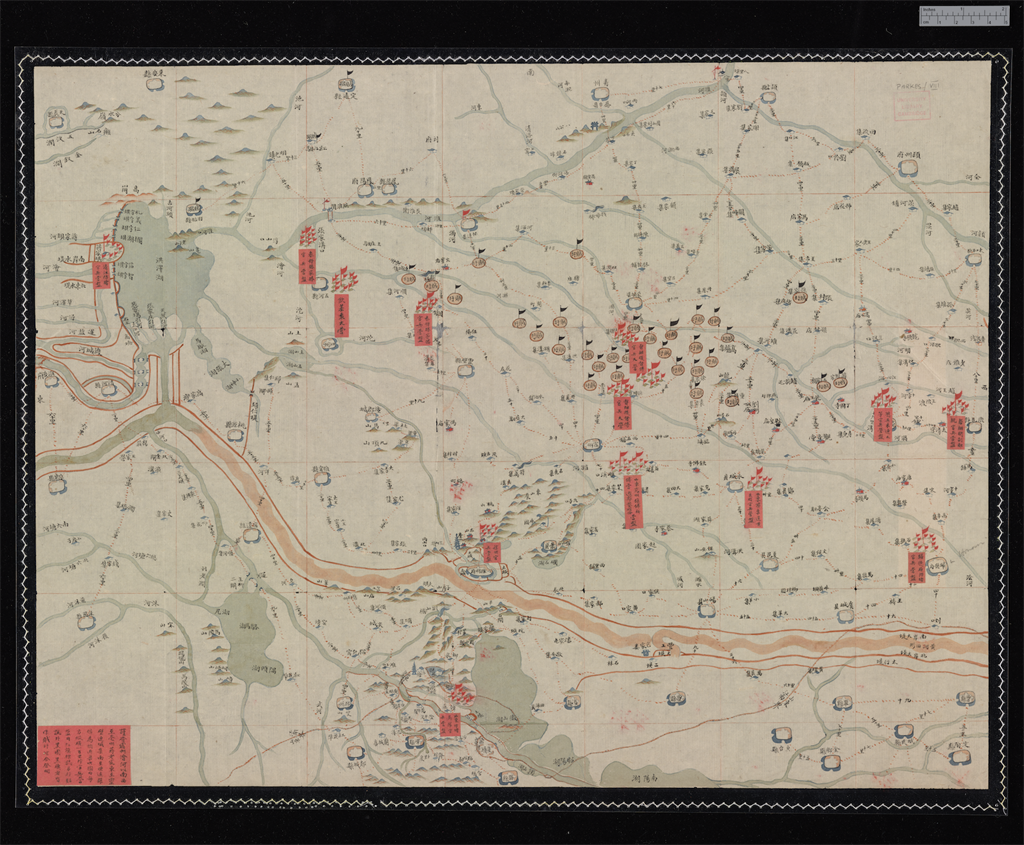

Both the Battle Scene of Nian Rebellionand another, different kind of map, the military map Huaibei dishi guanbing daying qingxing tu 淮北地勢官兵大營情形圖 (Map of the topographical and military situation of soldiers’ camps in the Huaibei region), tell narratives about the Nian Rebellion. Although the styles differ greatly, they both dwell within the same visual arena with maps like that of the Yellow River. For example, they both incorporate common practices of Chinese cartography: the inscriptions of place names according to their relative locations, the use of geographical texts as sources, the indication of distances between sites by “stops” (mountains, rivers, and houses), and the identification of the locations and changes to historical place names. These cartographic elements critically draw the military map closer to painted battle scene.

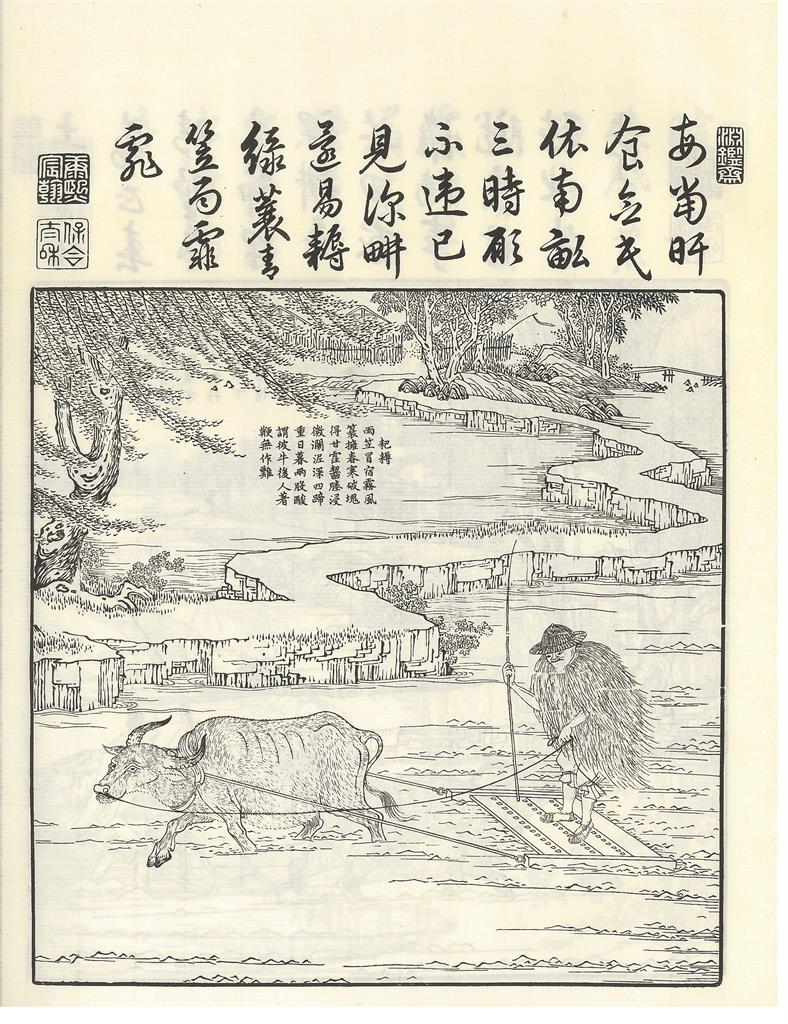

To return to the Battle Scene of the Nian Rebellion, though rendered so small as if to be trivial, the war refugees in the far distance in the upper right corner are noteworthy. On the one hand, they are leaving their homes for the purpose of moving away from the battle to protection provided by the court, but on the other, they are also abandoning their homes once so peaceful and calm. Perhaps the most famous of court illustrations of that pacific, indeed, idyllic life are the Gengzhi tu 耕織圖 or the Pictures of Tilling and Weaving, originally designed by the official Lou Shu (1090-1162) during the Southern Song dynasty (1127-1279). The Qing court early on commissioned a series of pictures bearing the same title. Their function is like that of the Battle Scene of Nian Rebellion: to transmit a sense of power and prosperity, as if the Qing court was in control of all under heaven (tianxia 天下).

In sum, in the Battle Scene of Nian Rebellion poses questions to which the pictures on display in “Mapping Motion” provide provisional answers. How does the painting look like a map? Indeed, what is a map? Can one write a connective history of battle scenes made at or for the Qing court from the fluorescent eighteenth century through the struggles of the nineteenth? How does the format and indeed the production of the pictures speak to the expanding (or contracting) authority of the court? What is the position of the viewer when taking in the painting of the Nian Rebellion? And what is it that actually is being mapped, after all? Military passage through a landscape of rebellion?The Qing court’s triumph? Or simply a form of political rhetoric?

Lisa Claypool and Wang Yue

Bibliography

Yee, Cordell. “Chinese cartography among the arts: Objectivity, subjectivity, representation.” In Cartography in traditional East and Southeast Asian societies. Eds. David Woodward and J.B. Harley, vol. 2, bk. 2: 128-169. London and Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994.

Zhang, Hongxing. “Studies in late Qing dynasty battle paintings.” Artibus Asiae60, no. 2 (2000): 265-96.

![Battle scene of Nian Rebellion [untitled].](/apix/Items/Image/101?guid=33b9c25144ad4821a27f83a21bfb73af&size=Large)